When my son turned seven, it was like a whole era of his childhood flashed before my eyes. The grounded Mother in me felt proud and nostalgic, the fear in me felt desperately driven to do all the things for him my mother did for me. That is, before it was ‘too late’ for him to appreciate it from that wide-eyed, reverent perspective which is reserved for the innocence of childhood (at least for economically privileged/white children). You know, those years when ‘sugar plums’ still ‘dance in our head’ as Christmas approaches. Last year, as Nutcracker season rolled around – I got tickets – unclear to be honest of my motivations, having not really thought about this production in what felt like ages. I wasn’t in the habit of looking back fondly on my childhood, where squeezed into itchy tights and suffocating satin dresses, I was the attractive ‘seen but not heard’ mascot of a middle child accompanying my family as we enjoyed each and every dying bastion of whiteness and ‘culture’ the upper middle class way.

Around eight years old I had a ballerina party complete with a towering, live blond ballerina and a plastic Barbie-ballerina popping out of the cake. I drafted blueprints of my future bedroom – all pink everything – which would soon be redecorated floor to ceiling with ballet-slipper themed wallpaper, matching bedsheets and curtains. The room of my eight-year-old dreams never came to be because by age nine, I was a full-throttle tomboy playing on all the local sports teams. If prima ballerina is a pipe dream all eight year old girls try on for size, by the following year, the only carrot of maturity I grasped for resembled the power and respect which I knew by now was clearly reserved for men only. I did experience the multiple eating disorders that accompany the body dysmorphic ballerina dream of youth, as gender-bending didn’t preclude the perfectionism, neuroses and self-loathing akin to becoming woman. Apparently, it’s the trifecta of growing up femme, and why many contemporary mothers are steering their daughters away from ballet altogether. As Sari Wilson, an ex-ballerina wrote for the New York Times, “For decades, I avoided ballet the way a recovering alcoholic avoids liquor” followed by, “When my daughter was born, my husband and I agreed she would not take ballet.”

By the time I moved to New York City in 2007, I was all about hip hop. What I perceived as its realness called to me on all levels. From the supposedly sexually empowered (if not sexually objectified) women to the honest expression of righteous rage – nothing else mattered to me so much or took up as much air time. Having grown up white-passing in the suburbs to sexually repressed parents, hip hop appeared to offer a brave world of body-positivity with an edge, loud female MCs speaking truth to power and the promise of embodied pleasure. And, the genre’s ostensibly ‘big booty hoes’ proved that I didn’t need to starve myself down to a size zero to be considered attractive.

A quick internet search reveals my intuitions are correct, The Nutcracker is racist. While it’s too corny for many a serious, aspiring dancer in the industry, it’s exotic depiction of non-white characters inside the wintery dreams of the white lead’s imaginary reads as cultural insensitive if not fetishistic. In a 2021 story about a Scottish dance company revising the Nutcracker to address racist underpinnings, The BBC confirms, “Created more than a century ago, its central characters are like the audience for which it was intended, wealthy and white.” Long story short, I cried through last year’s small town version of the Nutcracker out in New Jersey (where I could afford tickets) but fell in love with it this year when I took my son to The Brooklyn Nutcracker at the Theater at City Tech.

Touted as a “Christmas Love letter to the borough we call home,” this production says maybe ballet isn’t a lost cause after all. If glorifying all things white, transcendent and subsequently elite was never your cup of tea – you might enjoy the show too. Forgive me if it strikes you as limited an understanding of an art form which emerged from my native Italy, but as an intersectional feminist, ballet was simply another unhappy reminder of our racist and sexist society and the impossible standards it imposed on my body and mind. Maybe you’re thinking, does it have to always be so black and white? The answer is yes, and it’s complicated…

In The Black Dancing Body: A Geography from Coon to Cool dance theorist Brenda Dixon Gottschild compares and contrasts essential differences between African and European dance styles and aesthetic perspectives. In European styles, “The dancing body is dominated and ruled by the erect spine… limbs moving away from and returning to the vertical center, with a privileging of energy and gestures that reach upward and outward,” writes Gottschild. On the contrary, African-derived styles employ bare feet, use of the floor, grounded energy and articulation of the torso in ‘get down postures’ which draw attention to the pelvis, abdominals, breasts and buttocks and draw energy up from the Earth. European styles reach upwards (toward a transcendent male God in the Sky) and African styles drive down, in communion with the Mother Earth, the original God. In the terms of colonial racism, this is very much the basis of the ‘savage-versus-cultivated dialectic’ dichotomy in which African and European aesthetic principles became polarized along moral, spiritual and cultural grounds.

Gottschild cites Reverand Dr. Wyatt T. Walker who informs that continental Africa boasts over eleven hundred languages, none of which include a word for secular. In Africa, there is no distinction between spiritual and secular life just as there is no distinction between music and dance. Traditional African religions are danced religions, an effort by which the physical body achieves, in Gottschild’s words “Extraordinary flights of the spirit.” Christianity was prior to its rise as a monotheistic, orthodox religion, also a religion of song and dance. And depending on who you ask, Jesus was black and/or white. And yet, it was more advantageous for Europeans to disavow this part of their history, projecting it unto the racial other in order to justify the commodification of human life reinforced by negative racial stereotypes rooted in fear of the body/nature.

White European hegemony promoted both fear and restraint of buttocks power (especially the dancing buttocks) as sinful under the watchful eye of Christianity, ensuring amongst all else their own economic advantage as white folks. Such a sex-negative, anti-female worldview ironically promotes, in reverse, buttocks as a type of sexual epicenter as reflected in many ancient sacred perspectives which revere sex and sexual power as life-giving and cosmic. In her writing, Gottschild highlights how the tradition of the white and black dancing body in the West signifies a “clash between enculturated somatophobia [fear of the body] and embodied knowledge.”

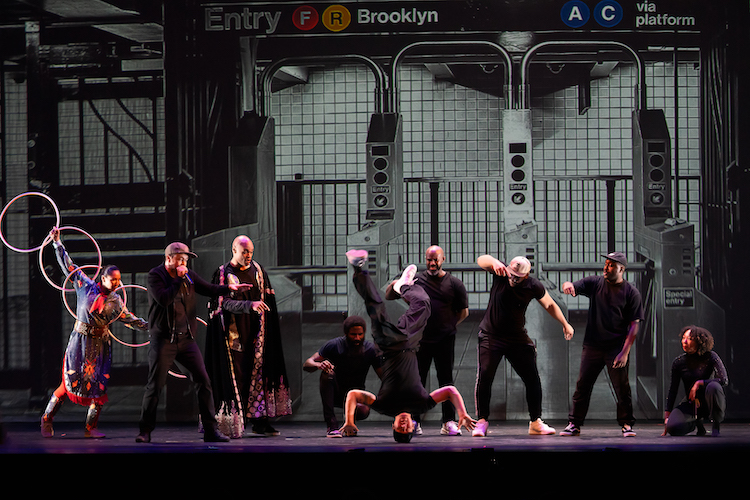

In The Brooklyn Nutcracker, running since 2010, we find much more depth and many more archetypes than one does in the classical version. Body types with bosoms too ample for dancing on toe and breaking crews that caused the crowd to erupt into applause, aka ‘clapping back’ with its multiple vernacular meanings. Although European styles have engineered their own superiority complex with respect to Godliness, church services long ago made it clear that the devout were to sit down, shut up and worship a god outside of themselves. A distinguishing factor in Black Diasporic music on the contrary, is call-and-response. While hip hop has exploded into a global music genre that still continues to sell out packed auditoriums, its original basis is the cypher (the circle) and five elements of art that situate it within a community-based, embodied, participatory framework. For while it might be inappropriate to call out at the opera, it’s a prerequisite at a rap show, where the MCs demand that audience members put their hands in the air and give thanks.

One distinguishing factor of The Brooklyn Nutcracker is that it’s not simply just a remix of an old European classic with a diverse cast of dancers paid to distill their cultural lineage into another white-approved spectacle. Gottschild calls this the laundering of “Appropriation-Approximation-Assimilation” which happens in the Arts mainstream as a matter of profit for some and survival for others. Nor was it a screen upon which persons of European heritage could project fantasies of the magical other. As a truly culturally immersive work, The Brooklyn Nutcracker transforms familiar Nutcracker characters and scenes to represent the heart of Brooklyn’s cultural mosaic with dance heritage roots in hip hop as well as other iconic global genres. While many of the major productions of the Nutcracker still employ trained ballet dancers to emulate traditional dance forms outside of their culture of origin, The Brooklyn Ballet highlights chief collaborators, giving them free reign to choreograph new works based on their dance lineage and mix and match their music of choice.

Tristan Grannum, a Brooklyn native that has played the ‘Snow King’ role for three years running, does triple time as a Brooklyn Ballet instructor involved in directing the Nutcracker production’s student and company dancers as well as serving as the Brooklyn Ballet’s Director of Community Outreach/Engagement. When I spoke with him by phone he remarked that even having performed in Nutcrackers around the country, this production was the first time he not only played a principle role, but could showcase his work to his friends and family here in his hometown. “I’ve grown into it as a dancer,” remarks Tristan, who shares that The Brooklyn Nutcracker’s ‘Snowflake Waltz’ is distinguished from other productions for its relatability, stating “Typically in the traditional show the Snow King and Queen are very regal. In our version it’s a little more pedestrian, I’m actually wearing a button-up and jeans. We are not figures that you can’t connect to.”

Scenes of The Brooklyn Nutcracker are framed by a backdrop of local landmarks, from the Flatbush Avenue subway platform to the Botanical Garden. Add to that a Bohemian Mother Ginger and techno tutus by NYC Resistor – a group who has pioneered motion sensor skirts and LED light projections triggered by the dancer’s movement on stage. At The Brooklyn Nutcracker, NYC Resistor’s experiments with motion sensor technology illuminate the more subtle pops, puffs, deflations and undulations of revered street dancer Big Mike as Herr Drosselmeyer. A leading hip hop educator and performer who has worked with Chaka Khan and Busta Rhymes, Michael “Big Mike” Fields aka Herr Drosselmeyer leads a daring hip hop battle scene wherein the traditional story’s army of mice trade rifles for hybrid street style moves involving a Krump Rat King in a lucid lock step dance battle.

Also in the spirit of tribal medicine dance, world-famous Native American Hoop Dancer ShanDien Sonwai LaRance gives the Nutcracker’s candy canes a run for their money spinning several 24-inch hoops in representations of an eagle, butterfly, flower and the Earth. Based on a traditional form of healing ceremony for restoring physical and emotional balance, LaRance embarks on a performance fusion blending native dancing with hip hop to a booming electronics-plus-powwow-drum track. Steve LaRance, proud parent of hoop dancers Nakotah and ShanDien, is quoted in an essay in the playbill explaining, “The hoop represents the turning of the season and the circle of life.” If ballet is about elevating out of this world to the fictional albeit privileged heights of whiteness, indigenous principles remind us we are each and everyone of us close to the divinity of nature and vulnerable to the cycle of life. In America, just as African Americans brought here during slavery were prohibited from using their drums and engaging in forms of danced worship, so too were Native American persons denied the freedom of conducting their ceremonial dances, although countless kept these sacred traditions alive in secret. As for the drum, Steve LaRance informs us how it represents the heartbeat, “It’s our connection to the ancestors and the Earth.”

After the hoop sequence, ShanDien Sonwai LaRance joined the cast’s crew of hip hop dancers playing the Flatbush Angels gliding, flexing, popping and locking (when not inserting their own take-offs on the ballet idiom) their way through various projected Brooklyn backdrops. In the scene’s culminating moment, LaRance, a Cirque de Soleil veteran, slithers off stage in a conga-line of sorts with the crew of Angels.

Later on, another crew emerges, this one a troupe of female dancers with long flowing extensions to their petal pink gowns. With offshoots of fabric resembling flowers waving too and fro, the group sways through the “Chinese Tea” in a sequence choreographed by Eva Bing Lu. In a culminating scene, award-winning dancer Aliesha ‘Pájaro’ Bryan delivers her Flamenco-style ‘Spanish Hot Chocolate’ choreography, a piece she’s been commissioned to create since 2018. Centered as a solo-dancer on stage, her sequence seemingly resurrects the Nutcracker’s long-lost Matriarch figure like the ghost of Christmas past. Bryan’s role in diversifying the Flamenco landscape includes starting her own extemporaneous venture – Blackbird Dances – a company that synthesizes depth psychology in movement with traditional Flamenco expressivity and digital space.

In the playbill essay “FLAMENCO: An Art of the African Diaspora” by Meira Goldberg, Spanish Hot Chocolate dancer Aliesha Bryan is characterized as “breaking time” by fellow dancer Asi-Kinen Al-Banna. That is, breaking in the sense of how the activating polyrhythms of Flamenco dance invites communion with multiple temporal dimensions. The essay explores how not only do Flamenco’s rhythmic complexities and soulful danced verse forms stem from Spanish colonialism and Afro-Islamic fusions brought about by force – the sacred communal dimensions of the art form nonetheless stand the test of time. With many many cultural effusions flowing in and out of the Spanish motherland and its colonial territories, today’s Flamenco is a living attestant to, “conceptions of the body, the breath and the voice as hosts for the divine” writes Goldberg.

All that being said, as The Brooklyn Nutcracker’s tiara-topped prima ballerinas emerged to do their signature solos (or were they duets?) I still felt deeply critical. Why, despite having just as many muscles in her highly sculpted physique, most of the time, did she seem to rely on a male partner, toppling side to side within his tether of security, or was it containment? Was this chiseled sidekick really the pinnacle of feminine achievement? While her body made all those lilting and ethereal shapes only achieved through years of intensive training, she could not stand on her own two feet. Just like the Barbies I played with as a child whose feet are designed for heels, not real life. Maybe herein lies the clamoring coldness of the original Nutcracker story – a fantasy about dolls come to life. Knowing the stakes of symbolic art where just as high as the ‘high brow’ world from which they emerged – I wanted to at least see a pro female ballet dancer as autonomous, strong and free. Was that too much to ask? Or was her gender tango with the male danseur a mirror of nature, ultimately about interdependence and the balance of opposites? A symbiosis of form and filigree?

In her MANIFESTO, Brooklyn Ballet Founder and Artistic Director Lynn Parkerson takes the spiritual approach to the genre, stating that ballet is an “Art form, a metaphor for the human spirit” with “time, space and music its crucible.” She writes that while it is an ever-evolving paradox, ballet embodies the “History of human relationship and musical structure.” Calling dance a ‘convent’ she writes that its outward manifestation as Art entails “Rituals purifying a technique unbound by personal theatrics,” so much that a “human vessel” becomes home to the “surging spirit and fire of God.”

Running approximate 2 hours, The Brooklyn Nutcracker graced CUNY’s the Theater at City Tech December 12-15th this year. In addition to its repertoire of convention-defying contemporary productions, The Brooklyn Ballet elevates community by providing in-school and after-school dance residency programs in under-resourced public schools. Brooklyn Ballet’s additional educational outreach efforts include projects like Take Ballet to the Streets – an outdoor performance series, Elevate & Brooklyn Ballet in the Houses. They also provide low-cost space rentals and performance opportunities to dance artists of NYC.

Learn more about the Brooklyn Nutcracker HERE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Black Dancing Body: A Geography from Coon to Cool by Brenda Dixon Gottschild, England: PALGRAVE (2003)

“My ‘Nutcracker’ Recovery” by Sari Wilson, The New York Times, December 17, 2015

“Scottish Ballet revises The Nutcracker to address racism” by Pauline McLean, BBC Scotland arts correspondent, published online December 4, 2021

“Community and tradition in the ‘Brooklyn Nutcracker’” by Stephanie Woodard, Dance Informa, published online December 16, 2016

“MANIFESTO” by Lynn Parkerson, Artistic Director, The Brooklyn Ballet website, published online September 7, 2002