Superwoman efforts of eclectic curators Atim Oton and Jiayoang Li, and gender activist Maiko Chitaia, go beyond the traditional art gallery system in surprising spaces and ways.

When African art industry leader Atim Oton closed the Harlem outpost of her Calabar Imports boutique and art gallery amidst pandemic challenges and more, her Crown Heights and Bed-Stuy locations carried on. The small storefronts on busy Brooklyn streets brought crowds of regulars for lively conversation and special events, but actual art sales remained slow.

Similarly, Chinese American writer and artist Jiaoyang Li found that the New Jersey location of her Accent Sisters “speakeasy” bookstore and gallery drew no foot traffic. And when Georgian immigrant Maiko Chitaia saw how much women in her country are unseen and unheard despite many struggles, she had no avenues to major media or public spaces to tell their stories.

These brave New Yorkers did not disappear. They pivoted and improvised in ways many can learn from past this Women’s History Month, when they all have current exhibits as well as spaces to patronize online and off. Here’s how these tireless women endeavor to continue in the tough business of uplifting women and artists.

1. A veteran unites with a name brand city staple.

Raised in Calabar, Nigeria, and completing graduate studies at London’s Architectural Graduate School, Atim Oton worked the design team for Manhattan’s African Burial Ground Interpretive Center. She founded public art initiatives in almost every borough. However, her labor of love Calabar Imports boutique and art gallery met the dwindling patronage and sales challenges most brick and mortar businesses do despite a one-of-a-kind handmade jewelry and clothing selection.

By 2023, she had scored exhibition space in a shared design studio in a Fashion District high rise. Now, she rests at street level in City Lore’s lower Manhattan headquarters, in an inventive rotation of her exhibits with theirs.

“Most of my art sales have been happening online for awhile,” says Oton. “But showing artists’ work in public and giving artists an audience in the world is vital to keep good art being made.”

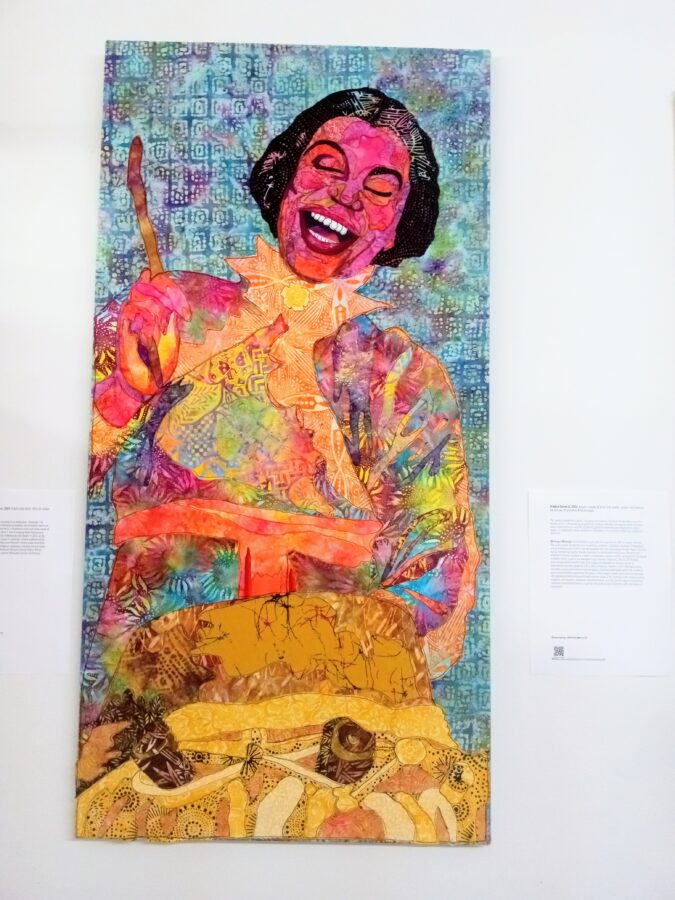

Located at 56 E. First Street off First Avenue, City Lore has showcased grassroots artists and provided free public arts programming for 40 years. Its administrative office sits behind its gallery space Calabar Gallery shares now. Oton and the organization alternate exhibits at roughly 6-week intervals. I visited for the opening of Oton’s last show, Why Flowers Bloom: Glass Art, Textiles, Paint and Mixed Media. The show featured the work of Ghislaine Sabiti, a French Congolese Brooklyn based glass, ceramics, textile artist; painter Sika Foyer, a Togolese Harlem-based mixed media, installation, sculptor, and fiber artist; and Rosy Petri, an African American, Milwaukee-based fiber artist. Other painters Oton represents were on display.

The show closed on March 21. Now, City Lore’s exhibit on New York City ballroom and drag queen history runs until early May. However, Atim catalogs all artists she represents and work left over from shows is still available for sale, and some is what she dubs “affordable” artwork under $1000. You may always shop this exhibit and more of Oton’s curation of African, African-American and Caribbean artists as well as jewelry and clothing at CalabarGallery.com.

2. A newcomer goes to the audience.

Poet and visual artist Jiaoyang Li co-founded Accent Society to give workshops and camaraderie to Chinese creatives in New York City and beyond. Experience as a resident poet at Chashama Gallery and as a small publisher had made her a growing name in Chinese art and culture. So Accent Society’s educational arm flourished with a small staff, but a physical Accent Sisters bookstore and gallery in New Jersey left Li in a quandary: Rent was affordable, but no customers came to buy. Like Oton, Li knew she had to come closer to a target audience in Manhattan.

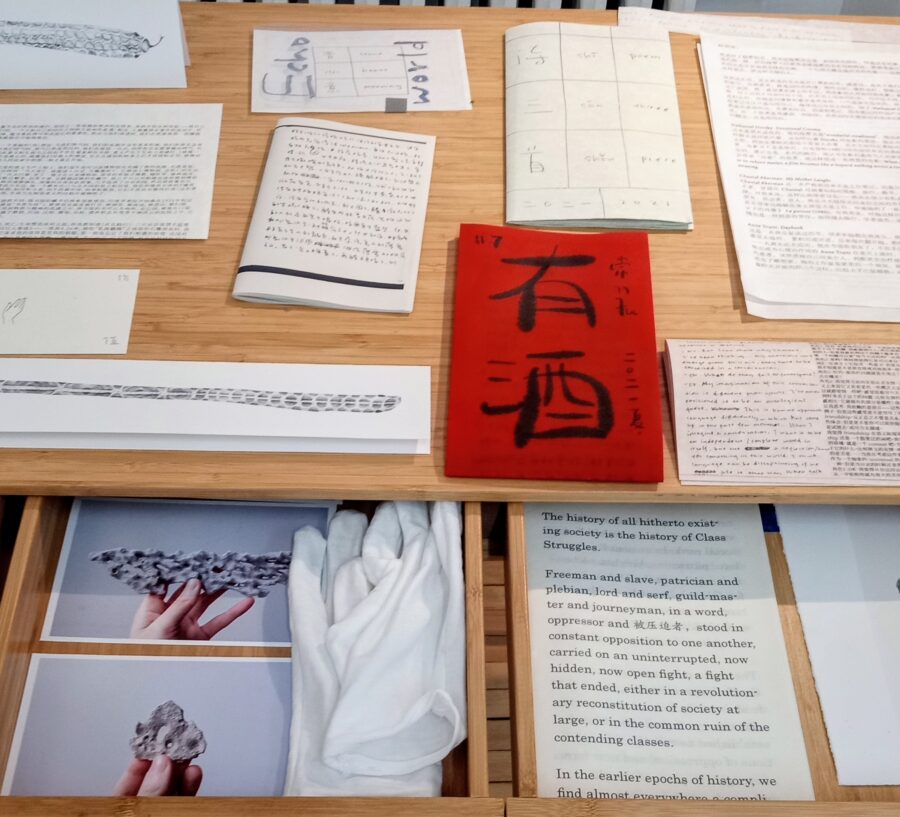

Recently, her exhibit 39 Footnotes opened in a new space on the 7th floor of a 5th Avenue office building off Union Square. United in the theme “Mother Tongue,” the exhibit displays installations and paintings by Li and others, all surrounded by books written in Chinese for sale. The exhibit runs until May and will also include short film screenings throughout the spring. Li even plans on a fashion show of emerging Asian designers soon.

“People just couldn’t get out to Jersey so we had to move to the people or close,” Li said. “Here we are having great turnout for events and people can come in everyday even if we are not here.”

Her purpose to support women especially was evident at 39 Footnotes’s March opening, where Li granted a pop-up bar to the Fuzhou Sisters to serve their cult following Quinhong rice wine.

This summer, Li will publish her first novel-length book, Winifred Wang’s coming-of-age debut Dissection of the Moon. She hopes to add author readings to the list of happenings at the Accent Sisters space. To meet her there and keep up with exhibits, follow @AccentSisters on Instagram.

3. An immigrant builds a killa website for global exposure.

Georgia slips away from most when thinking of European countries. Gender researcher and communications specialist Maiko Chitaia wanted to change that, especially for women like her who call it home. Dismayed by how many Georgian women’s stories of struggle she saw outside traditional media, Chitaia got busy. Unable to fund a documentary and needing to give voice to a diverse cross section of women throughout the country, her Women of Georgia website was born.

The now New York-based Chitaia is a co-founder and co-author of the website’s testimonies from over a hundred women who range in age from teen to senior years. Her collaborators include professional writers and photographers to produce often the first formal headshot many featured women have ever had. With most interviewees in Georgia’s Tbilisi capitol but many abroad, the site’s survival narratives come from the depth of homelessness to final destination nursing homes. Chiataia soon discovered how necessary her decision was to take these women’s stories online in absence of other outlets or media interest.

“We found a disabled woman with no job or income and nowhere to go, but her story spread from our site and donations saved her,” Chitaia recalls. “We do this for no money, but grants and book sales help.”

Chitaia and her team lament an uncertain future given the current dismantling of government programs supported by USAID, one of the project’s largest funders (UN Women is another big support). To support the project, explore the site including multimedia or video and consider buying the book To See the Invisible: Stories of Women with Disabilities from Georgia.