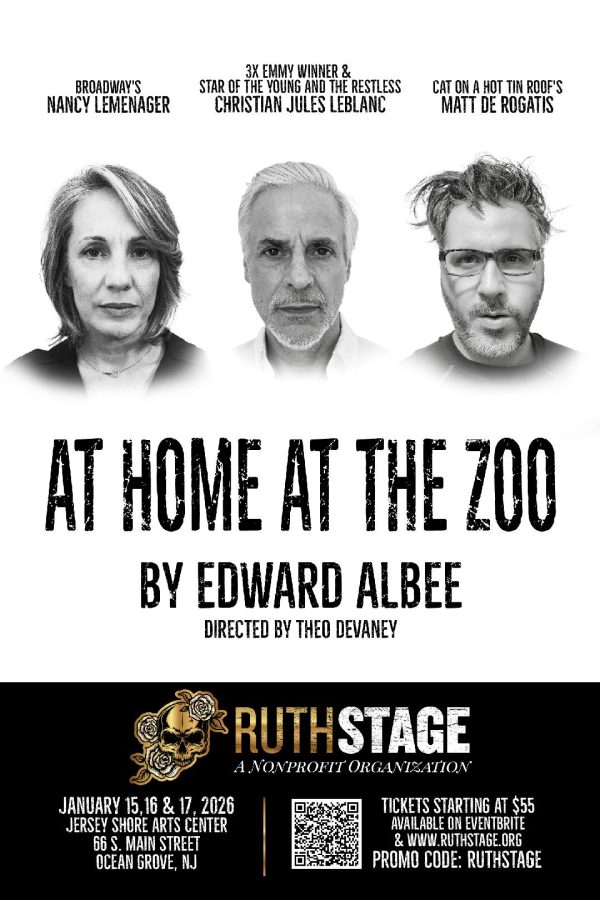

Beauty News NYC’s Q&A with Matt de Rogatis reveals the latest on his new role in “At Home at the Zoo,” from his process to approaching the character of Jerry to what he hopes audiences take away from this production, and more! We last covered Matt de Rogatis in Ruth Stage’s “Lone Star,” and prior to that, we featured his role in another Ruth Stage production of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” which even extended due to early success! Now he’s back in a new role, and we can’t wait to see him do his thing come January!

“At Home at the Zoo” brings Albee’s Homelife and The Zoo Story together in full form, something audiences rarely get to experience. As an actor, how does performing the complete emotional journey of Jerry reshape or deepen your interpretation of him?

Well, interestingly, the addition of “Homelife” does not include the character of Jerry at all — it’s entirely focused on Peter and his marriage. When Albee wrote “The Zoo Story” in 1958, he later felt Peter was somewhat underdeveloped, so in 2005, he created “Homelife” to expand Peter’s emotional depth and give audiences a clearer sense of who he is before the famous park bench encounter.

What’s funny is, even though I’m also producing the show through Ruth Stage, I’ve chosen not to read Act I. If I did, I might form opinions about Peter that Jerry really shouldn’t know. “The Zoo Story” is ultimately two strangers colliding by chance, so even though we’re now giving audiences the full Albee experience, I think it’s best that Matt only knows what Jerry knows.

For Jerry’s sake.

You’ve played Jerry before in Ruth Stage’s September production of “The Zoo Story.” What felt unfinished or still “alive” in that performance that made you want to revisit the character through this expanded two-act version?

Well, this is a great question — and I think the answer is something a lot of actors would echo. If I’m doing my job correctly, I’m not “playing” a role so much as creating a living, breathing human being. And if that’s the case, I don’t think any human being is ever really finished. We’re always evolving, absorbing new experiences, discovering new parts of ourselves. Characters function the same way.

I’ve played many roles dozens of times over the years, and every night something shifts — a moment lands differently, a line reveals a new meaning, my scene partner gives me something unexpected. That’s the beauty of live theater.

When we did “The Zoo Story” in September, it was only a three-performance run. And Jerry is such a rich, layered creation — his major monologue is one of the longest ever written for an actor. There’s simply no way to feel “complete” with a character like that after only a few shows. I honestly feel like I’ve only scratched the surface of who this man is.

Even with “At Home at the Zoo” being only three performances again, I suspect I’ll still feel like there’s more to uncover. I’m not sure any character is ever truly finished. There’s always another layer.

This revival features an extraordinary trio: you, Nancy Lemenager, and Emmy winner Christian Jules LeBlanc. How has working with artists from Broadway, Hollywood, and Off-Broadway influenced the energy and texture of the production?

What’s been extraordinary about this process is the combination of talent and experience in the room. I’ve worked with Christian Jules LeBlanc for several years now — he played Big Daddy opposite me in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” we performed together at the Tennessee Williams Festival in New Orleans, and of course we shared the stage again in “The Zoo Story” this past September. We have a natural rapport, both onstage and off, and at this point I don’t even think of him first as an Emmy winner; I think of him as my friend Christian. But the truth is, he is an Emmy winner — and one of the most beloved soap actors of the last three decades. His presence brings an enormous amount of attention to what we’re doing. In September, we had people travel from ten different states, including Texas, to see the show, largely because of the connection they feel to him.

Nancy Lemenager brings that same level of artistry from the Broadway world. She’s performed on Broadway ten times, and from the moment she auditioned, it was obvious she was the right person for this role. Our director, Theo Devaney, keeps telling me how extraordinary she is in rehearsals. She’s one of those actors who elevates the room simply by doing the work at the highest level.

What excites me is that none of this is stunt casting. We’re not bringing in names for the sake of names. These are artists whose talent speaks for itself, and the fact that they happen to be Broadway veterans or national TV stars is a bonus — one that helps Ruth Stage grow, because it gives audiences access to Broadway-caliber and Emmy-winning performances right here at the Jersey Shore.

Working alongside actors of this caliber pushes me to grow and elevates the entire production. It also reinforces what makes Ruth Stage unique. We’ve built a reputation for dangerous, psychologically charged reinterpretations of classic works, and that artistic identity attracts artists who are excited by that challenge. Having people like Christian and Nancy want to be part of what we’re creating is a testament to the quality of the work.

And honestly, I think the combination of our rapport, the rarity of this two-act version of Albee’s play, and the talent in the room has set the stage for what might be one of the strongest productions Ruth Stage has ever produced.

Theo Devaney is an Oxford-trained director with a deep background in both classical theater and film. What has he brought to this staging that feels distinctly his?

What Theo brings to this production is something truly rare. We throw around words like “amazing” so casually now that they’ve almost lost meaning — but Theo genuinely earns it. He’s one of the most insightful directors I’ve ever worked with.

My mentor, Bob Lamb, always told me that a great director doesn’t tell you what to do — they guide you. That’s Theo in a nutshell. He studies what you’re doing, understands where your instincts are taking you, and then offers adjustments that feel organic and deeply perceptive. And the thing is, when he suggests something, ninety-nine times out of a hundred, it just works. It elevates the moment. It sharpens what you’re doing.

Working with him feels like watching a master mechanic at the top of his craft. He’ll come in, tighten something here, reposition something there, clean up a tiny detail that you didn’t even realize was cluttering the scene — and suddenly the entire engine runs cleaner. It’s subtle, precise, and incredibly effective.

But what makes Theo distinct isn’t just his intelligence or his Oxford training — it’s his generosity. He cares deeply about his actors, he cares about the work, and he cares about honoring the psychological complexity of the material. He sees connections in the text and in human behavior that simply don’t cross my mind until he points them out, and that’s the kind of director who makes you better.

I mean it when I say he’s one of the best directors I’ve ever worked with, and if we continue collaborating — and I hope we do — I wouldn’t be surprised if he becomes the best. This production is stronger because of him.

Albee’s writing in this piece explores masculinity, loneliness, domesticity, and the human need to be witnessed. Which theme resonates most deeply with you at this moment in your career and why?

What resonates most with me isn’t one single theme — it’s the entire psychological landscape Albee creates. “At Home at the Zoo” is exactly the kind of material Ruth Stage gravitates toward: stories where the human condition is laid bare, where the emotional wounds inside the text are impossible to ignore.

Our mission is to reimagine classic works through a psychological lens — trauma, personality disorders, depression, shame, alcoholism, PTSD. Every character carries something fractured within them, and that’s where we tend to live as a company. Pain is universal, even if the circumstances that create it are unique. We all know loneliness. We all know the ache for connection. We all know the need to be witnessed.

Because I’m a man and I often lead the creative charge, there’s naturally a strong thread of deconstructed masculinity running through our productions. But that doesn’t mean the women in these plays aren’t equally complex and wounded — Amanda Wingfield, Maggie the Cat — they all carry their own storms. Albee is no different. His writing is a psychological minefield and the female character of Ann goes through this in Homelife, the first act of this production.

So it’s not that one theme hits me harder than the others right now. It’s that this play, as a whole, is so deeply aligned with what I’m trying to explore as an actor and what we’re trying to build at Ruth Stage. The loneliness, the quiet desperation of a failing marriage, the violent spiritual hunger inside Jerry — all of it speaks directly to who we are as a company and the kind of emotional excavation we want audiences to experience.

This piece lets us take people into a psychological vortex — and that, more than any single theme, is what resonates with me most.

Ruth Stage has described its work as “emotionally raw” and focused on excavating trauma, identity, and human behavior. What emotional or psychological spaces does this role demand that other iconic roles of yours — like Brick or Frederick Clegg — have not?

It’s funny you mention Frederick Clegg, because he’s one of the most complex characters I’ve ever played, and in some ways he and Jerry share certain spiritual wounds — the loneliness, the outsider status, the desperate need for connection. But the psychological spaces they occupy couldn’t be more different.

Clegg is a sociopathic killer whose trauma curdles into violence. He ends The Collector almost exhilarated, ready to do it again. Brick, in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” is drowning in self-destruction, but he still has a family, a home, a Maggie — there’s a faint glimmer that he might find his way back as the play concludes.

Jerry is different. Jerry is someone who has already lost the fight.

I don’t think I’ve ever played a character this destitute, this spiritually depleted, this close to the edge of life. Albee gives you these extraordinary monologues where Jerry describes the circumstances of his rooming house — the smells, the bodies, the claustrophobia. You can feel the poverty, the despair, the absence of hope. Jerry is a man who doesn’t see a future. He’s either looking for someone to save him or someone to finish him — and on any given night, I’m not sure he knows which.

That’s the emotional terrain this role demands: taking someone the world would normally dismiss as “a burden,” “a bum,” “someone to avoid,” and pulling the audience so far inside his pain that they find themselves sympathizing with a man they would cross the street to avoid in real life.

That’s the challenge.

That’s the responsibility.

That’s the psychological excavation.

I want people to walk away feeling the tragedy of a life that could never quite connect. Not, “thank God that guy’s off the street,” but “God… what a loss. What a human being we never bothered to see.”

There are a lot of Jerry’s in the world.

Most people ignore them.

This role asks me to make you care about one.

The park-bench confrontation in “The Zoo Story” is legendary. With the addition of “Homelife,” audiences now witness what comes before that encounter. How does Act I change the stakes or urgency of Act II for you as a performer?

The park-bench confrontation in “The Zoo Story” is legendary. With the addition of “Homelife,” audiences now witness what comes before that encounter. How does Act I change the stakes or urgency of Act II for you as a performer?

Honestly, the addition of “Homelife” doesn’t change the stakes for me at all — and that’s very intentional. Jerry doesn’t appear in Act 1, and he has no knowledge of what happens inside Peter’s home. So from my perspective as the actor playing Jerry, nothing about his inner life, his urgency, or his psychology shifts. I’m still entering “The Zoo Story” exactly as Albee originally wrote it: a stranger walking up to a man on a bench with a lifetime of pain behind him and absolutely no idea what he’s about to walk into.

Where the stakes do change is for Peter — and for the audience.

“Homelife” was written decades after “The Zoo Story” because Albee felt Peter was underdeveloped. He was an everyman, almost a symbolic figure. With Act 1 added, we now see the fractures in Peter’s marriage, the suffocating domesticity, the emotional paralysis that pushes him out of his apartment and onto that bench. Christian Jules LeBlanc now gets to carry all of that into Act 2, and it profoundly alters the audience’s experience of the confrontation.

So while nothing changes for Jerry — because it can’t and it shouldn’t — everything changes around him. The audience sits down for Act 2 with a deeper understanding of who Peter is, what he’s running from, and why this encounter matters. It reframes the bench scene without altering its core.

In that sense, “At Home at the Zoo” doesn’t raise the stakes for Jerry — it raises the stakes for everyone watching him walk toward Peter.

Ruth Stage is building a multi-year residency in Asbury Park with an eye toward future NYC transfers. As Chairman and Creative Director, what excites you most about this moment artistically — not just for you, but for the company as a whole?

What excites me most about this moment is that we’re not relocating — we’re expanding. Ruth Stage has spent years building a reputation in New York for reimagining classics with a visceral, psychological edge. Now, we get to bring that same energy into a community that already has a deep artistic heartbeat. Asbury Park is a cultural hub — music, visual art, food, counterculture, history — and I feel like our rebellious brand of theatre fits seamlessly into that landscape. I mean, the city’s nickname is literally “The Dark City.” That’s Ruth Stage territory.

Artistically, this is the first time in our company’s history where growth isn’t theoretical — it’s tangible. We’re establishing a residency, engaging in talkbacks, partnering with local businesses, and building real relationships with the community. That kind of direct exchange with audiences is invaluable. Asbury gives us something New York can’t always offer: space to develop, experiment, and take risks without being constrained by the brutal economics of the city.

Not every show we do here will transfer to New York, and that’s the point. Asbury is becoming our laboratory — our out-of-town tryout, our farm system. We can build three, four, even five productions a year here, shape them with audience feedback, and take the strongest ones into the Off-Broadway arena. For the Asbury audience, it becomes “see it here first,” and for New York, it means a more refined, more dangerous version of the work we incubate.

For me personally, what’s most exciting is that this residency represents the culmination of years of hard work — and the beginning of something much larger. Our donors, sponsors, and supporters have helped us reach a place where Ruth Stage is no longer a boutique theatre company — we’re becoming a force, a brand people need to pay attention to. And honestly, I’m not done. Asbury is step one. There are other cities and states I want to bring this kind of theatre to. This is the start of a multi-year expansion, not the end of one.

You’ve built a reputation in New York for bringing a visceral, dangerous edge to classic works. What do you hope audiences walk away with after experiencing “At Home at the Zoo” in this intimate Jersey Shore setting?

What I hope audiences walk away with is a feeling — not a polite reaction, not “that was a nice little production,” but something visceral. I want them to sit in their seats for a moment afterward and think, “What did I just experience? I think I need a drink!” Whether we’re playing Off-Broadway under Times Square billboards or in an intimate space at the Jersey Shore, my goal is the same: emotion, intensity, danger.

Pro wrestling has influenced my life so much in the way that I run Ruth Stage and in the way I create. That art form is built entirely around emotional connection, whether the crowd loves you or hates you. Indifference is the only failure. That’s what made our production of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” so successful. It was polarizing because we brought it into the 21st century and re-introduced people to characters they thought they already knew. Some people loved it. Some people didn’t. But everyone felt something. If someone walks out of a Ruth Stage production feeling nothing, then we didn’t do our job.

With “At Home at the Zoo,” audiences are watching three lives quietly—and violently—deconstruct in front of them. In Homelife, you see the silent wounds of a marriage that’s slipping away, which so many people will recognize. And then you collide with Jerry in “The Zoo Story,” who carries core wounds of loneliness, trauma, and a desperate need for connection. He’s one step away from the streets, but what he feels and is going through is something everyone has touched at some point.

I want the audience’s heart rate elevated. I want them leaning forward, not knowing what’s coming next. I want them to lose themselves in the experience the same way the actors do. When people walk out saying, “I need a minute,” that’s success to me. That means we didn’t just present a play — we created an event.

And no matter the venue, I want people leaving the theatre thinking, “Ruth Stage is a force. They always make me feel something.”

For fans discovering you through this production — people who may only know you from “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” — what should they know about Jerry and why this character matters to you?

For people who only know me from “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” stepping into Jerry is going to feel like meeting an entirely different human being. That’s important to me, because I’ve never believed acting is about repeating a persona or a “type.” It’s about surrender. It’s about letting yourself disappear and allowing another person—someone with his own history, wounds, desires, and contradictions—to take your place for a while.

Jerry matters to me because he represents the kind of characters Ruth Stage gravitates toward: men who are fractured, masculine identities that have been broken down, rebuilt, and broken again. There’s trauma in him, there’s loneliness, there’s a kind of existential ache that I think a lot of people carry quietly. I’m fascinated by that. I study it. I break it apart psychologically.

Each role I take on, whether it’s Brick, Tom Wingfield, Richard III, or now Jerry, asks me to tap into a different part of myself — sometimes parts I didn’t know were there. These characters aren’t just roles; they’re mirrors. They force me to confront things in myself as I bring them to life.

What I hope is that when someone who’s seen me as Brick walks into “At Home at the Zoo,” they don’t see any trace of that man. I want them to see someone unrecognizable, not because of makeup or affectation, but because I’ve allowed myself to fully inhabit another psyche. Jerry is messy, wounded, volatile, and human — and that’s why he matters.

“At Home at the Zoo” is playing at Jersey Shore Arts Center January 15th, 16th, and 17th!

Theatregoers can purchase tickets to “At Home at the Zoo” at ruthstage.org or HERE.

Use PROMO CODE: RUTHSTAGE for a discount.